T his is a blog post by Patrick Präg on a paper we recently published. Patrick is a researcher at Oxford University’s Department of Sociology and a Fellow at Nuffield College. Patrick holds a PhD in Sociology from the Interuniversity Center for Social Science Theory and Methodology (ICS)/University of Groningen in The Netherlands and does research on social inequalities and how they affect the lives of individuals. Follow Patrick on Twitter: @ppraeg

his is a blog post by Patrick Präg on a paper we recently published. Patrick is a researcher at Oxford University’s Department of Sociology and a Fellow at Nuffield College. Patrick holds a PhD in Sociology from the Interuniversity Center for Social Science Theory and Methodology (ICS)/University of Groningen in The Netherlands and does research on social inequalities and how they affect the lives of individuals. Follow Patrick on Twitter: @ppraeg

Health care in the United States is a controversial topic nowadays, and for good reason: On average, Americans have worse health than people from similarly rich countries, despite the fact that the US health care system is more expensive than any other health care system. What is more, there are also large health differences between Americans from different regions of the country.

These features make the US a particularly interesting case to study the relationship between education and health. We know that individuals with more education are generally healthier than those with less education, yet we don’t fully understand why this is the case. Some reasons are well-established: Higher income buys better health care and the better-educated behave healthier. But this does not necessarily explain why health differences between the lower and the higher educated are smaller in some places than in others. What is different in places where educational groups are more alike than in others? To understand what is driving differences in the relation between education and health, researchers have long been comparing health differences between countries or between regions of a country.

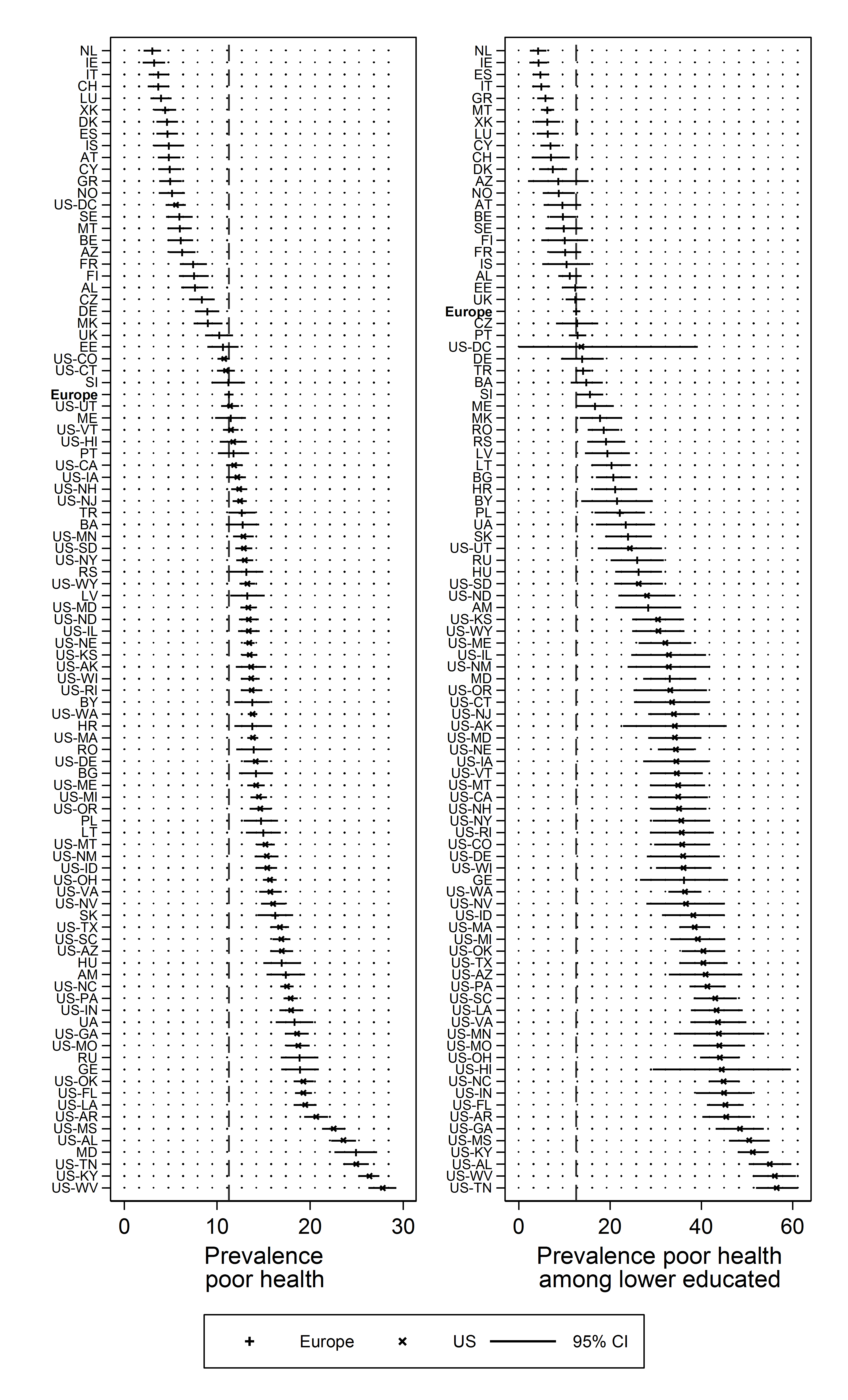

In our study, we decided to compare Americans’ self-reports of poor health to those of Europeans from 44 countries, distinguishing Americans by the federal state they are living in. This generated some striking findings. As we expected, Americans are reporting worse health than Europeans, and differences in the US are large. Around eleven per cent of Americans from Connecticut report poor health (that’s the European average), for West Virginia, it is almost 30 per cent. But we also find that health differences between educational groups vary in the US. Almost sixty per cent of lower educated Americans in Tennessee report poor health, around twice as much as the lower educated in Utah.

Next to this variation, it is striking that educational health differences in the US are comparable to those of the poorest countries in Europe, namely the countries in Eastern Europe. Thus, our studies gives important impulses for current and future research on health inequalities, it also emphasizes the importance of comprehensive health care reform in the United States.